Hommage de A. Peron

à Gustave Cotteau

|

B I O G R A P H I C A L N O T E on Gustave COTTEAU by A. PERON ____________

I

Towards the middle of last August, when the geological

world was working and celebrating and when three great scientific

meetings, the congress of the French association in Caen, the

extraordinary session of the Geological Society in Lyons and the

international congress of geology in Zurich, were attracting and

dispersing all the geologists, news as painful as it was unexpected,

published by all the newspapers, suddenly spread and brought mourning to

the midst of these meetings. Gustave Cotteau, who was expected there, had

just died, carried off in a few moments by a devastating illness.

The very next day, recognising the impossibility of getting

proper treatment in the simple pied-à-terre he had in Paris, Cotteau had

himself taken to the nursing home of the Brothers Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, rue

Oudinot, no. 19. He believed, at the time, that he would only have to stay

there for a few days, and he had written to his brother, who was then in

Belgium, and to his nephews, not to worry and not to be disturbed. Unfortunately, the recovery took longer than he thought. The swelling in his leg did not go down and reduced him to inactivity and immobility, which, for a man used to an active and industrious life like himself, was a real torment.

So, despite the many visits he received from family and friends, he endured the stay in the care home very impatiently.

It was at this time, on 27 July, that I saw him for the last time. At his request, I stayed with him for a long time, talking to him about his troubles, his projects and his work in progress.

Nothing at that moment, absolutely nothing, could seriously alarm us. Our friend was not suffering at all. Not a word came out of his mouth that would indicate any preoccupation on his part with an impending end. He was only sorry for his forced inactivity and impatient with the delay in his recovery, which obliged him to give up his plans to travel to Caen, Zurich, etc.

A few days later, a slight improvement occurred and our friend was able to start walking a little on the arm of his doctor.

He had to be given ether and transported to his deckchair.

This postcard and telegram, written carefully and in a firm hand, were given by Cotteau, at about five o'clock, to his nephew, Colonel Georges Vial, who was to follow him so closely into the grave.

However, the doctor had shortly left the house when he was called back to tell him that the patient had suddenly succumbed. He had been struck by a cerebral congestion in his recliner at about 6 o'clock, when he had just started his meal.

II Such, gentlemen, were the last moments of the eminent scholar whose life you have charged me to trace. The news of his death, so unexpected, caused a real shock among his many friends. From all sides, the most touching letters, full of real sorrow, poured in to show his family how keen the general emotion was and how painfully the loss of this man of heart was felt everywhere.

His funeral was celebrated in Auxerre, in the midst of a large crowd of the entire population. Several remarkable speeches were made at his grave, notably by Messrs Ernest Petit and Rabé, the vice-presidents of the Yonne Society of Sciences, who were able, in eloquent and moving terms, to show us the immensity of the loss we had just suffered.

Cotteau was not only esteemed and justly regarded as a man

of science, but he was also cordially loved by all those who had the good

fortune to know him. One of the most striking features of his character

was his inexhaustible goodness, his courteous affability, his unfailing

benevolence and helpfulness. He was very indulgent to everyone and very welcoming to young people, and knew how to encourage and reward their efforts with a kind word.

In the many reviews he published during congresses and scientific meetings, he never had a single word of derogatory criticism for the authors. His analyses, true models of clarity, concise exposition and measure, always knew how to bring out the value of the communications with benevolence. His discussions, always courteous, shed light on the issues and, at times, re-established the facts without the slightest offence to the authors. He was therefore welcomed everywhere with joy, and when he appeared at a meeting, all faces expressed contentment and all hands reached out to him eagerly.

His loyal and conciliatory character, his deep feeling for the dignity of science had earned him universal esteem. It was because of this esteem that he was often chosen as an arbitrator and intermediary to settle those small quarrels or disagreements which sometimes arise between scholars.

III Gustave Cotteau was born on 17 December 1818. He was therefore in his seventy-sixth year when death struck him. Many people, on learning this age from the letters of announcement, expressed deep astonishment. It was difficult, indeed, to attribute such an age to him when one saw him so active and alert, constantly facing long and tiring journeys, always filled with an indefatigable ardour for work and a lively and youthful animation in his conversation and speeches. Our colleague, in fact, had the rare privilege of preserving to the end, not only his physical vigour and health, but also all his brilliant faculties, his ease of work and elocution, his happy memory, his lively intelligence and, something even rarer, even his excellent eyesight, an instrument of work so precious to him, which was able to withstand the incessant use of the magnifying glass and the immoderate overwork imposed on him by the special nature of his research. Gustave Cotteau's health was not always so good, however. On several occasions, it was severely shaken. In the spring of 1881, in particular, our colleague was struck by a serious case of pneumonia which put him at the brink of the grave and which did not seem likely to leave him with such long days. It was at this time that, faced with this serious situation, he made his testamentary dispositions which you know and which, since that moment, have never changed.

Gustave Cotteau was born in Auxerre, in a house at about

number 43 rue de Paris, where his family had rented a flat. However, his

parents lived in the village of Châtel-Censoir, and it was in this pretty

country, with its deep valleys and thickly forested hills, in this

picturesque part of the Yonne valley, that his childhood years passed. He did his classical studies at the college of Auxerre and, having been destined to enter the judiciary, he then went to Paris to study law. It was during this stay in Paris that our colleague's vocation as a geologist and echinologist seems to have been established. A newspaper of the Yonne, the Indépendant Auxerrois (n° of August 30, 1894), published, on this subject, under the title "the chance of a vocation", a curious anecdote which was, it says, addressed to him by Mr. L. V., the learned professor of the Museum, friend of our late fellow-member. The story is a little too long for us to reproduce it verbatim, but it is too interesting for us not to give at least a summary. While studying law in Paris, Gustave Cotteau is said to have entered an auction house one day by chance. His attention was drawn to a small box containing crystals and shells of unusual shapes, and he wanted to buy it to decorate his student room, where he thought it would have an artistic effect. He put a very modest price on this lot, but he found himself up against a competitor and an auction battle ensued in which he emerged the winner. His competitor, an elderly decorated man, was astonished to see such a young man competing for such a prize. He approached him while he was examining the contents of his box, and engaged him in conversation by asking him if he was interested in natural history. Cotteau replied that he had no interest in natural history and explained the purpose of his acquisition. If that is so," said the stranger, "consent to give me two or three of your samples which interest me, and in return I will give you others no less decorative. Cotteau hastened to leave these samples with him and the stranger, handing him his card, invited him to come and see him, promising to show him his collection and to determine his fossils. This competitor was none other than Mr Michelin, a councillor at the Court of Auditors, a great amateur, as we know, of Echinids and Polyps.. Cotteau did not fail to keep his appointment, and Michelin, who was very welcoming, gave him advice and initiated him into the knowledge of sea urchins. Although I am not in a position, through personal information, to guarantee the authenticity of this episode in Cotteau's scientific life and I have found no trace of it in his correspondence with Michelin, I cannot, because of the provenance attributed to it, doubt its veracity. Cependant j'ai la conviction que la part faite au hasard dans ce récit est trop grande et trop exclusive. Il est évident pour moi que, dès cette époque, Cotteau était un curieux des choses de la nature et qu'il devait déjà avoir quelque connaissance des fossiles. Le pays qu'il avant habité, le milieu où il avait vécu n'avaient pas été sans exercer sur lui une certaine influence sous ce rapport. Dès son enfance, il recueillait dans les environs de Châtel-Censoir des Insectes, des Mollusques vivants et sans doute aussi des fossiles et des Oursins qui, dans cette localité, étaient si abondants et si beaux qu'un observateur comme lui ne pouvait pas n'en être pas frappé. hese research habits seem, moreover, to have been a long-standing tradition at Auxerre College. To be convinced of this, I need only refer to my own childhood. There were many of us among the pupils of this college who collected fossils or shells. The rich and numerous quarries which existed around the city were often the goal of our walks. Several of our teachers collected fossils, encouraged our research and sometimes even took the product from us. It did not take much more to determine or develop a taste for this kind of study in young people whose spirit of observation and natural curiosity predisposed them to it. I do not believe therefore that chance and the desire to decorate his room artistically alone led Gustave Cotteau to acquire a batch of fossils at the auction house. From that moment on, I am convinced that he had scientific tastes, the need to obtain study materials, and the sacred fire that he showed all his life. Perhaps, at the time of his meeting with Michelin, Cotteau was already a member of the Geological Society of France; indeed, at the age of 21, when he was a student, he was appointed a member of the Society and it was not, as one might think from the incident we have just described, Michelin who introduced him to it, but other sponsors.

IV On 25 August 1840, Cotteau defended his thesis for the degree of licentiate in law. He then returned to Yonne, dividing his time between Châtel-Censoir and Auxerre, until he was appointed deputy judge in the latter town on 6 March 1846. This period of his life was laboriously filled with various researches and studies for the development of his knowledge in natural history.

At that time his vocation as an echinologist was definitively fixed. The active correspondence he was already exchanging with the masters of the science proves this abundantly. Davidson, in a letter dated 1844, said to him: "Since you like sea urchins so much, I reserve for you a Cidaris adorned with its quills....". Michelin, on the same date, wrote to him: "I always think of you for sea urchins....". The same was true of Hébert, Orbigny, M. Crosse, etc.

It was also in 1847, and in this same work, that he published his first memoir on the Echinids, an interesting early work, which we will discuss in some detail later on.

Mr Duru, his uncle and father-in-law, was in fact an eminent collector himself. An enlightened lover of the ceramic arts, of various antiquities, of paintings, of rare manuscripts and booklets, he had also, at the instigation, probably, of his nephew, become involved in conchyliology. He succeeded, through important purchases, travels and exchanges, in assembling a remarkable collection of shells from the present day.

V Gustave Cotteau's first stay in Auxerre did not last long. By decree of September 23, 1851, he was appointed substitute at Bar-sur-Aube. He stayed only two years in this new residence, but this short time was nevertheless well used by him for science. In the vicinity of Bar-sur-Aube, he carried out active research and, in 1854, he was able to publish a notice on the Echnids of the Kimmeridgian stage of the Aube department. He had been, as soon as he arrived, appointed member of the Society of Agriculture, Sciences and Arts of this department and, a little later, at the time of the scientific congress held in Troyes, in 1865, he published a reasoned catalog of the Echinids of Aube.

In November 1853, Cotteau was appointed judge at the civil

court of Coulommiers. This appointment, which took him away from his

family and sent him to a country not very favorable to his studies, was

received by him with some regret. He accepted it only in the hope of

seeing his seat promptly transferred to the court of Auxerre and, indeed,

he left his collections in the latter city and settled only temporarily in

Coulommiers.

Independently of the continuation of his studies on the

fossils of the Yonne, he published his Echinides du département de la

Sarthe, numerous notes on geology and on sea urchins, the first fascicles

of his new or little known Echinides, reports on the progress of geology

in France, etc.; it was also during this period that he was able to

publish a number of other works. It was also during this period that, as

we will say later, he undertook the continuation of Alcide d'Orbigny's

French Paleontology, a gigantic work which was to occupy him until his

last hour. VI

By decree of August 11, 1862, Cotteau was finally appointed

judge of the civil court of Auxerre. This appointment, so long awaited,

filled him and his family with joy, and he hastened to settle in his

beloved native land, which from then on he was never to leave.

I was then returning from Corsica where, as I said, Cotteau

himself had made a trip, and I brought back from a rather long stay on

different points of the coast an abundant collection of marine animals and

especially of those beautiful fossil sea urchins that one finds on the

cliffs of Liceto and Santa-Manza, near Bonifacio. It is by the common

examination of all these materials, used later by him and by M. Locard,

that our relations began seriously. Cotteau had just moved into his beautiful and comfortable home on Rue du Réservoir. Most of you, gentlemen, know this hospitable home. It is there, in this property provided with admirable gardens and spacious premises, specially arranged to receive the various collections, that the life of our fellow-member passed. It is there that, since that time, all these scientific and artistic treasures accumulated, which he knew, as a scientist, an artist and a man of taste, how to arrange so admirably.

How many good and pleasant days were spent there. How many times scholars have gathered there in numbers, constituting real small congresses. What good talks then! What lively discussions on the questions of the day, on the recently published works, on the small events of the scientific world! Our colleague was a conversationalist who knew how to interest and charm. His knowledge in all things, his travels, his extensive relations in the learned world and the correspondence he maintained with the scientific notabilities of all nations, fed his conversation and made it as attractive as it was instructive. Great days of pleasure were also those when we went with him to search the ravines and quarries. The numerous visitors he guided in our surroundings will certainly not contradict me when I say how pleasant and interesting the excursions with him were in these circumstances. He was familiar with the smallest details of our foundations, the smallest corners of our quarries, but the information he was able to give was not limited to these local details. His knowledge of many other regions allowed him to compare and generalize the facts, and it was then real practical lessons that he gave on the field to his companions of excursion. Sometimes we had the good fortune to meet at his place his brother, Mr. Edmond Cotteau, back from one of his great journeys, and then his so interesting and varied stories were a charming distraction to our geological talks. In his absence, moreover, Cotteau loved to read his brother's letters to us, true travel journals, dated from all parts of the world and filled with ever new facts, curious details and moving incidents. He was passionate about reading these letters and knew how to make them even more attractive by his animation and the interest he took in them.

At other times, he had to read us less serious letters and

tell us the small anecdotal facts of his correspondence.

It was sometimes a collector who sent him, under the name

of petrified children's limbs, flints of the chalk with strange forms and

who asked him to confirm this determination. Sometimes it was another correspondent who, having learned that our fellow-member, independently of the fossils, had a collection of living sea-urchins, asked him seriously how he did to feed them.Un autre enfin, en lui envoyant des Oursins et voulant, suivant les recommandations, préciser les conditions du gisement, expliquait avec détails que tous ces Oursins avaient été trouvés sur le versant sud de la colline, lequel étant plus chaud et mieux ensoleillé que le versant nord, convenait mieux, sans doute à leur développement.

Cotteau answered all these questions with perfect and

meritorious helpfulness. His principle was that researchers should always be encouraged, and that by directing them properly and patiently, one could always expect serious services. VII

I have just spoken, gentlemen, about the considerable

scientific correspondence of our fellow-member. From the beginning he has

carefully preserved it. With an excusable curiosity, I allowed myself to go through a part of it, especially the old letters, emanating from the old and venerated masters who are not among us anymore. How interesting is the reading of these letters where the whole history of geology, echinology and archaeology unfolds for more than half a century! One finds there the echo of all the great discussions which agitated the scientific world and sometimes also of all the small quarrels which divided it.Plus de 300 noms, parmi lesquels ceux de toutes les notabilités scientifiques, sont signés au bas de ces lettres, témoignant de l'étendue des relations de Cotteau dans le monde entier. Qu'on me permette de citer particulièrement les lettres très affectueuses de d'Orbigny, dont la plus ancienne qui soit entre mes mains remonte à 1841, puis celles de Michelin, d'Agassiz, de des Moulins, de Desor, de Lovén, etc., où l'on voit se développer l'échinologie et que complètent les lettres plus récentes de nos confrères qui aujourd'hui continuent l'œuvre de ces anciens maîtres, notamment celles de M. de Loriol, l'un des meilleurs et des plus intimes amis de Cotteau, de M. Gauthier, devenu depuis longtemps son collaborateur, et de M. Lambert, son compatriote et un peu son disciple. It is still the voluminous correspondence of Triger, sometimes lively and malicious, but always filled with details and particularly interesting stratigraphic discussions; that also considerable of Davidson, marked by an ardent zeal for science and where one finds curious information on our own country; that of Hébert, whose triple quality of great scholar, compatriot and former student of Cotteau, sufficiently explains the interest which one finds there and the great intimacy which reigns there; then the letters of the count de Saporta, this eminent fellow-member whose recent loss we deplore, and where I want to note only his strong urgings to bring Cotteau to the study of the fossil plants and the hope which he had one moment to succeed in it. I want to quote again among the most precious, the numerous letters of de Caumont, the devoted director of the Institute of the provinces, where one attends the organization of all the scientific Congresses held in the various cities of France and where one sees what important role Cotteau filled there; then those of M. Crosse, always witty and playful and full of amusing anecdotes; those of Bayle, sometimes biting, but always of a pleasant originality, in which the eminent professor treated the scientific questions in a very humorous way, demonstrating for example to Cotteau that it was not necessary to pronounce Ekinides, or Rhynkonelles, but well Echinides and Rhynchonelles because we say "cornichon" and not "cornikon". Bayle's talent as a draughtsman was given free rein in these letters. Depending on the subject, his initials represented a Mammoth, a Gastropod, a Diceras or a Sea Urchin, and the name of the signatory was perched, in microscopic characters, at the end of the Elephant's tail, at the end of the Gastropod's spire or at that of a Sea Urchin's radiolus, which he jokingly called Microcidaris Baylisans. One of the things that strikes one most when reading these letters is the trust and affection that all his correspondents show to our colleague. Beginning, as it usually happens, with requests for communications, exchanges or determinations, the relations with him are quickly consolidated and established on a footing of frank mutual friendship. Nothing is more to the praise of Cotteau than these universal testimonies of esteem and sympathy that, from all sides, attracted him his frank and loyal character and the safety of his relations.

VIII

The years that followed Gustave Cotteau's installation in

Auxerre were not all happy days. On several occasions he was cruelly

tested. Towards the end of 1865, he was struck down in his most cherished affections. His beloved companion, this devoted and enlightened woman who contributed so powerfully to the charm of his house, was suddenly taken from him, as well as the child she had just given birth to, after eighteen years of a sterile marriage.En 1868, il perdit son beau-père, M. Duru, le zélé collectionneur dont nous avons déjà parlé, qui s'était si fructueusement associé à ses recherches : puis, dans cette même année, un nouveau deuil vint encore jeter l'affliction dans sa vie. Sa sœur bien-aimée, Madame de Vaux, lui fut à son tour ravie, à la suite d'une longue et douloureuse maladie. These terrible ordeals destroyed the courage of our friend for a long time. However, in spite of these cruel losses, he remained happily divided in terms of family. He was able to keep his father until 1874 and he found in the affection of his brother-in-law, M. de Vaux and his children and in that of his brother a powerful consolation.

Gustave Cotteau had a deep affection for his brother

Edmond. Older than him of about fifteen years, he had seen him growing up

and had, since childhood, associated him to his researches in the

surroundings of Châtel-Censoir. Later, when Edmond Cotteau had become the

intrepid traveler, whose fame is universal, and when his travel stories,

so instructive and so endearing, had obtained from the general public the

success that we know and from the French Academy one of its most envied

rewards, our colleague was prouder of it than of his own successes, and

one of his greatest pleasures was to talk about it to his friends.

Freed from any obligation unrelated to science, and well-favored in terms of fortune, he could devote himself entirely to his studies. We see him, from this moment, the assiduous guest of all the congresses and all the great scientific meetings, abroad as well as in France; we see him, to be more in the center of the scientific movement, taking a residence in Paris and dividing from then on his time between his residence of Auxerre, where he prepared and wrote his works, and that of Paris, where he supervised their material execution.

IX

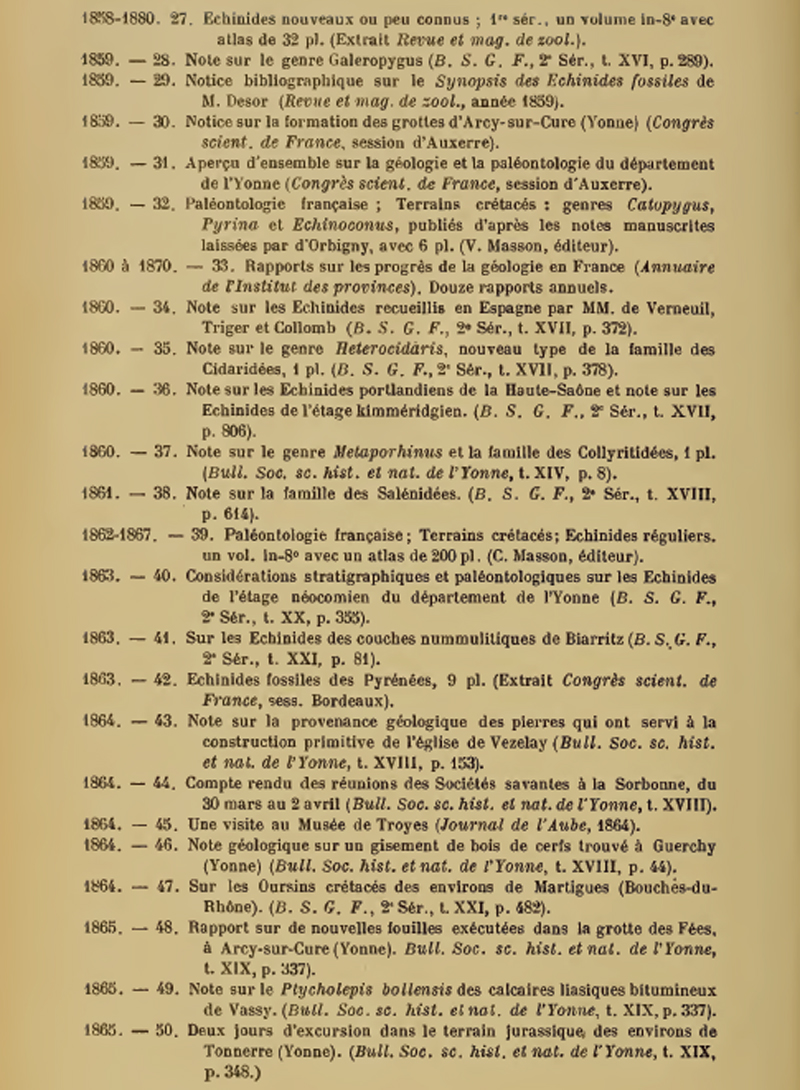

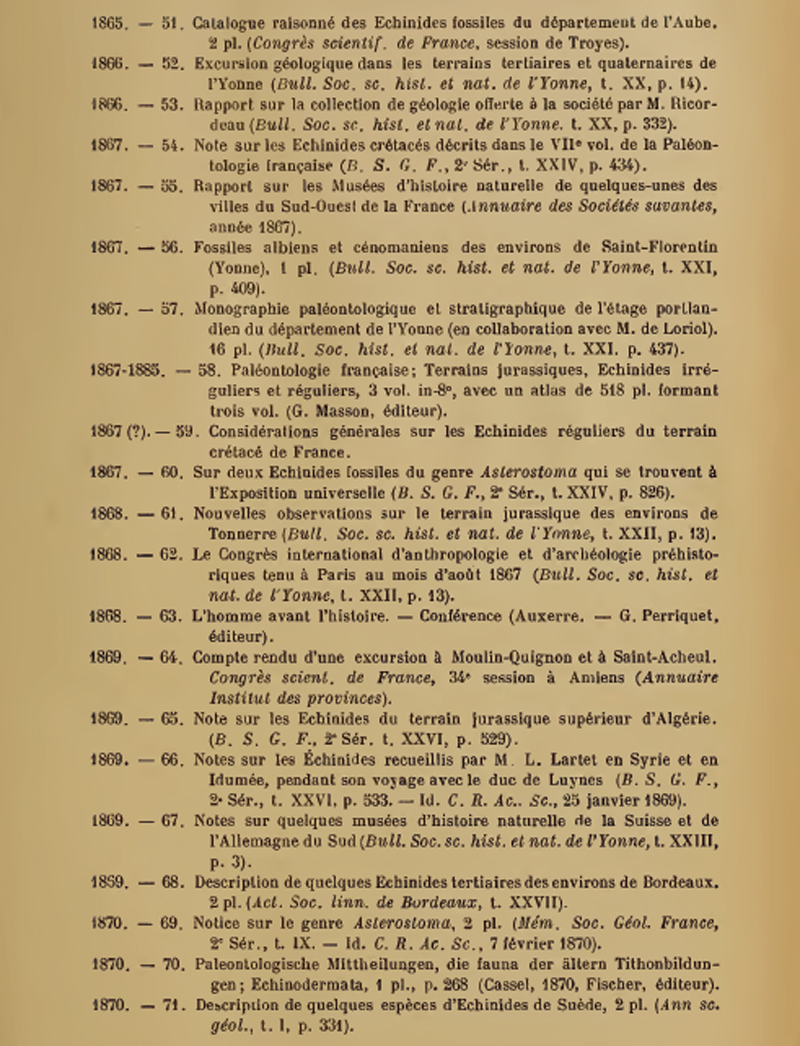

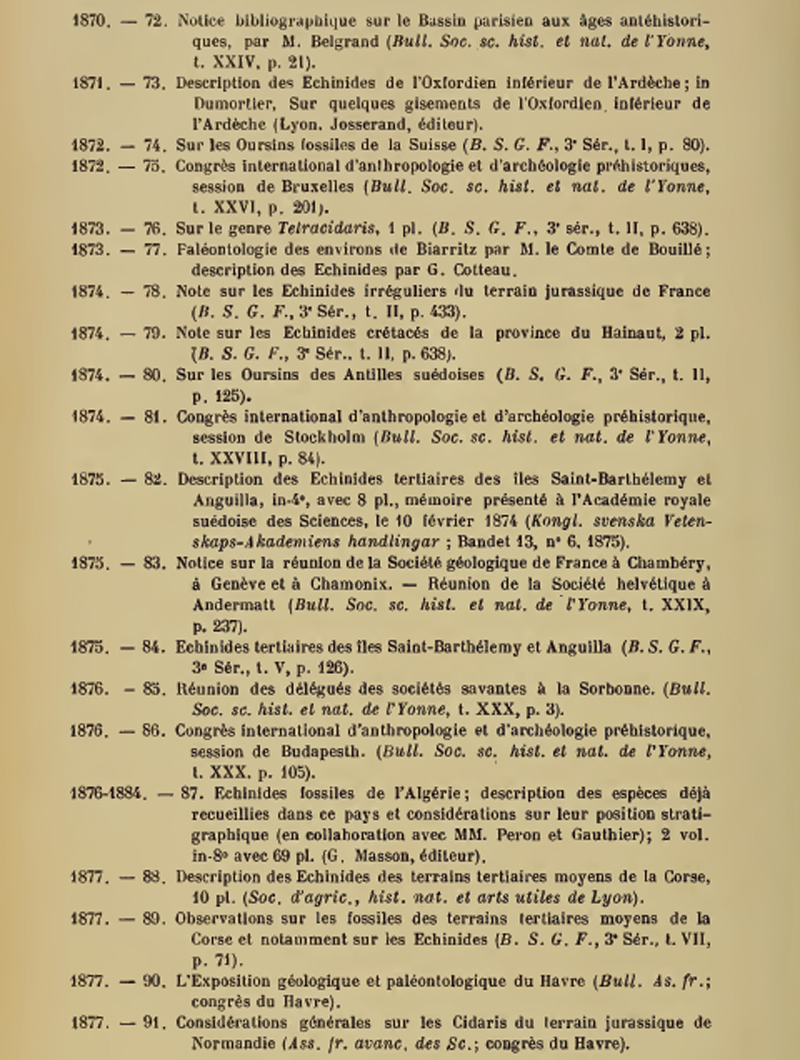

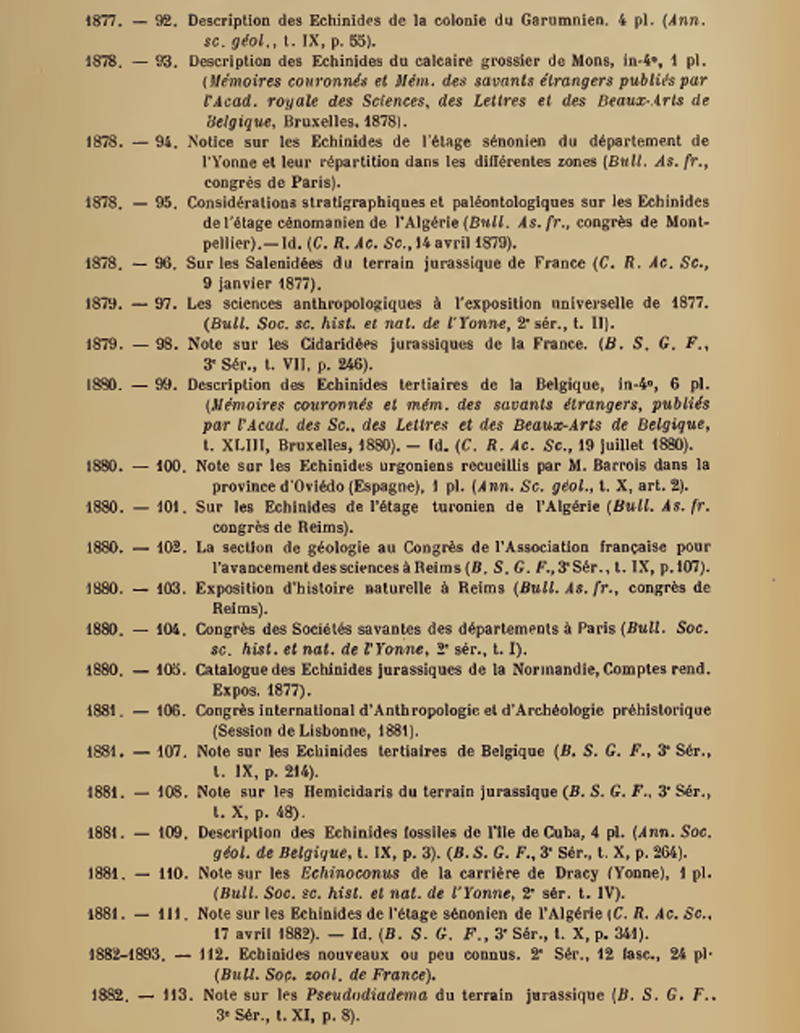

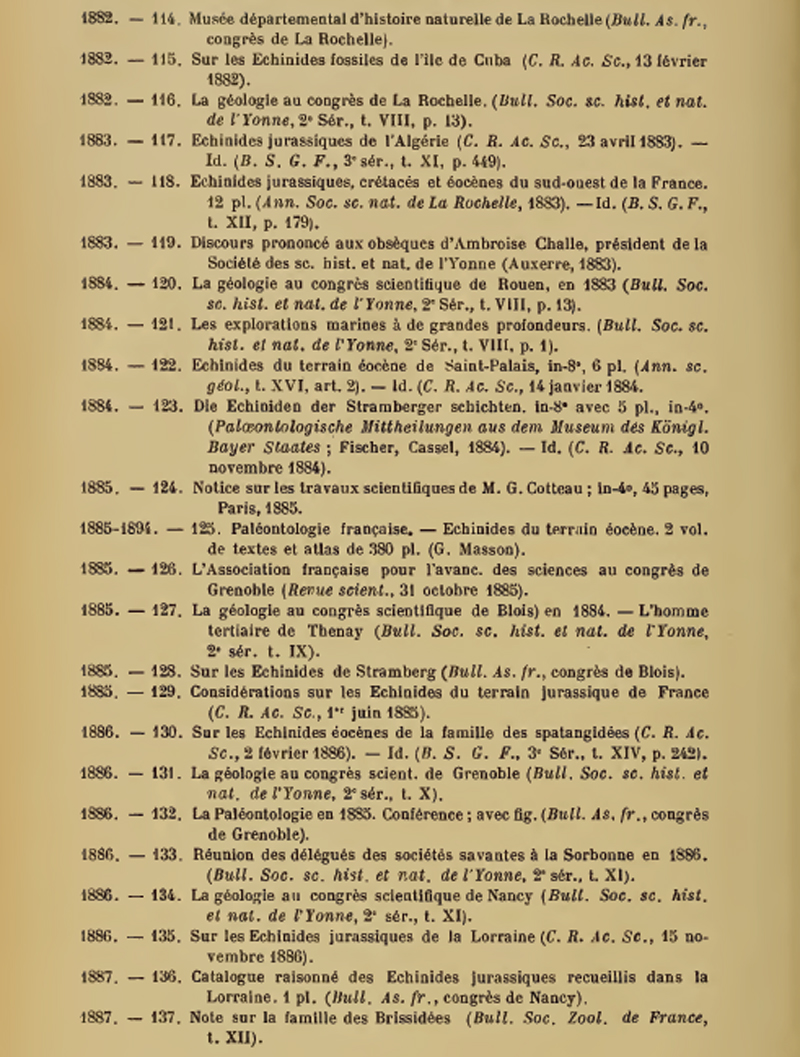

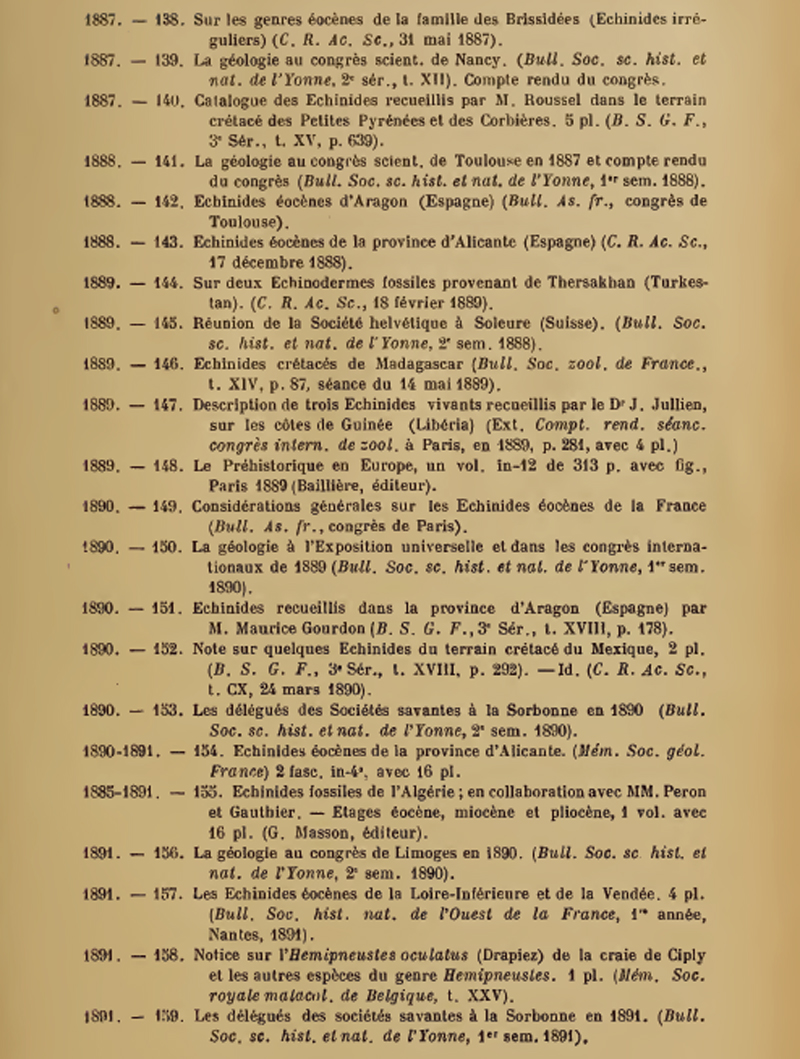

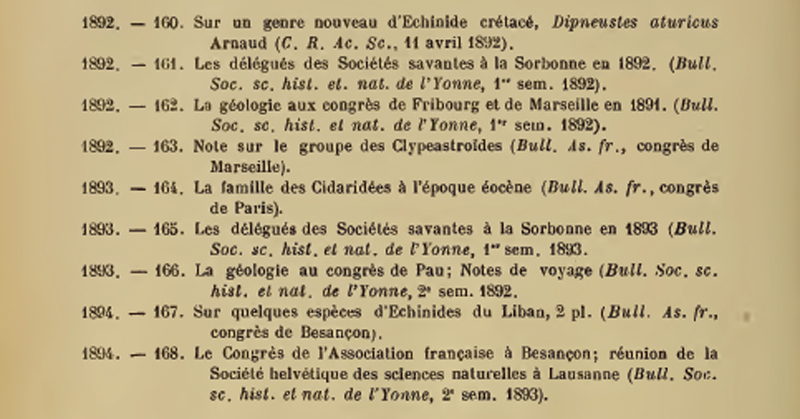

The work of Gustave Cotteau is enormous. It is the product

of a ceaseless work during fifty years of a life filled with science, and

it has acquired a truly exceptional importance. The catalog that I have

drawn up and which is annexed to the present notice includes no less than

168 numbers, and often separate notes, but related to the same subject,

have been put together under the same number.

It is easy to understand that it is not possible to

undertake, within the restricted framework of a simple note, a detailed

analysis of such a work. Cotteau himself, moreover, has given us, for his

works prior to 1885, a very substantial summary, written naturally with a

knowledge of the subject that one could not ask for better, and at the

same time with a simplicity and modesty that we must admire. The first works of G. Cotteau were purely literary. As early as 1836 he published in the newspapers and in the Annuaire de l'Yonne some pieces of poetry which were noticed. But these works go beyond our field and we cannot stop there.

It was in 1844, more than 50 years ago, that his first

scientific works appeared. They were geological notes on the surroundings

of Chatel-Censoir and on the department of Yonne, in particular on the

Oxfordian layers and on the Aptian terrain, then, shortly afterwards,

studies on the coral massif, on the erratic blocks, etc.

In 1847, we see his first work on the Echinids. It was

inserted in the Bulletin de la Société des Sciences de l'Yonne under the

title of "Note sur le Dysaster Michelini". This small work of our fellow-member deserves that one stops there a few moments, not only because it was his beginning in the study of Echinids, but because it was the origin of a courteous but animated discussion which started between him and Michelin, and in which were mixed other echinologists, Desor and Agassiz.Michelin, en effet, qui, quelques années auparavant, avait, conformément à l'idée émise par Agassiz, adopté le genre Metaporhinus précisément pour l'Oursin en question ne pouvait admettre que notre confrère l'eut placé dans le genre Dysaster.

In a long correspondence, he explained the reasons and

fought against the way of seeing of Desor and Orbigny to which Cotteau had

rallied.

Michelin won his case in this discussion. Cotteau after

having, in the genus Metaporhinus, returned on his opinion following new

finds which allowed him to better discern the distinctive characters of

these sea urchins and, in 1860, in a new note on the genus Metaporhinus

and the family Collyritidae, he adopted and justified completely the way

of seeing of Michelin. The first important work that Cotteau published was his Etudes sur les Echinides fossiles de l'Yonne. Begun in 1849 and published in installments in the Bulletin de la Société des Sciences de l'Yonne, these studies were not completed until 1876. However, the publication of the first volume, which was completed in 1856 and which made known all these beautiful Urchins of the Corallian of the Yonne, where our fellow-member discovered more than 50 species, was enough to establish, from that moment, his reputation as an echinologist.Dès 1853, Desor lui écrivait : "Ce n'est certes pas une flatterie de vous dire que pour s'occuper d'une manière sérieuse et avec fruit de l'étude des Oursins, il est indispensable de vous connaître et de vous étudier. Voici bien des mois que votre ouvrage est sur ma table, à côté de moi, en compagnie de ceux de MM. Forbes, Gras, Quenstedt, etc., et il ne se passe pas de jours que je ne vous consulte."

Almost immediately after his first volume of the Oursins de

l'Yonne, G. Cotteau published another work, no less important, the

Echinids of the department of Sarthe, which he had undertaken at the

urging of Triger and with his collaboration in what concerns the

stratigraphy.

It was the publication of this beautiful work which, at

that time, designated him to the attention of the scholars for the

continuation of the French Paleontology of Alcide d'Orbigny. At the time of the death of our great paleontologist, in fact, the volume of Irregular Cretaceous Echinids was being published. It remained to publish, on this volume, the genera Catopygus, Pyrina and Echinocononus, on which d'Orbigny had left handwritten notes that it was necessary to coordinate and complete.Dès 1857, notre éminent confrère, M. le professeur Albert Gaudry, beau-frès de d'Orbigny, fit des ouvertures à Cotteau pour la continuation de son oeuvre. Cette première démarche toutefois ne fut pas suivie d'effet immédiat. Des négociations s'étant ouvertes pour l'acquisition de la Paléontologie française par l'un de nos grands éditeurs, M. Gaudry dut retirer sa proposition.

Gustave Cotteau, however, was eager to undertake this

beautiful work whose high importance and renown, already universal,

pleased his ardor; but, following the acquisition of the work by M.

Masson, he had a moment of uncertainty on the question of its

continuation. He had heard that proposals had been made to Desor on this

subject, and, not wishing to compete with him, he asked him frankly and

loyally what was the matter, assuring him that he would applaud

wholeheartedly if the fact were correct.

In a letter as laudatory as it was affectionate, Desor

declared that no proposal had been made to him, that Cotteau, who knew the

Oursins better than anyone else, was naturally designated for this work

and that, in the very interest of the work, it was to be hoped that one

would stick to the first project. Following these talks, in 1859, M. Masson charged Cotteau with the completion of the volume of Irregular Echinids. Then, in the meantime, in June 1860, on the initiative of the highest scientific authorities, a committee of specialists, all members of the Geological Society, was formed to continue the work of d'Orbigny.Cotteau, appelé à en faire partie, en devint bientôt le membre le plus actif et le plus zélé. Après la fin des Echinides irréguliers crétacés il publia les réguliers de ce terrain en un volume de 892 pages avec un atlas de 200 planches. Puis, de 1867 à 1885, il publia tous les Echinides jurassiques, occupant 3 volumes de texte et 518 planches, et, de 1885 à 1894, les Echinides éocènes en 2 volumes et 384 planches.

All that remained to complete this colossal work was to

make known the Echinids of the middle and upper Tertiary terrain. M.

Masson, for whom French paleontology had long since become a rather heavy

burden, did not want to undertake this last publication. However, out of

friendship for Cotteau and at his insistence, he finally agreed. Already

our fellow-member, with a haste that justified only too much his advanced

age, calling upon all the researchers, had gathered considerable materials.

More than 80 persons or museums had sent him their Miocene

sea urchins. Already the first issue was composed and printed in proofs,

the plates were drawn, when death suddenly came to stop the publication.

It even seems that, unless there are very special

circumstances, French paleontology is finished. As M. Masson recently told me, Cotteau has taken with him to the grave not only the volume of Miocene Echinids but also any continuation of the great work of d'Orbigny.Telle qu'elle est cependant, la part de Cotteau dans ce gigantesque travail n'en constitue pas moins l'une des monographies les plus importantes qui aient jamais été publiées. Elle a fait le plus grand honneur à la science française et, grâce à notre ami, la classe des Echinides, l'une des plus ignorées jusque-là, est actuellement l'une de celles qui rendent le plus de services à la géologie.

However much work was required for the preparation of such

a work, it is not necessary that Cotteau limit his efforts to this

publication. The few issues that he was able to publish annually were far

from sufficient for his activity, so he published many other works

simultaneously.

As far as echinoids are concerned, one can say that he

studied those of all parts of the world. For those of France, independently of the annual fascicles that he published on new or little known sea urchins of all origins and after his descriptions of the Echinids of the Yonne and those of the Sarthe, he published special monographs on those of the Aube, the Pyrenees, of the Haute-Marne, of the Haute-Saône, of the Bouches-du-Rhône, of the Ardèche, of Biarritz, of the Garumnien, of the Lorraine, of the Corbières, of Corsica, of the South-West of France, of Normandy, of the surroundings of Bordeaux, of Saint-Palais, of the Loire-Inférieure and the Vendée, of Algeria, etc.A l'étranger, il étudia ceux de la Palestine, de la Syrie, de la province du Hainaut, de la Suède, des Antilles suédoises, du calcaire de Mons, des terrains tertiaires de Belgique, de l'île de Cuba, des Karpates (Stramberg), du Mexique, de Madagascar, du Liban, du Turkestan, et, en Espagne, ceux de la province d'Oviédo, ceux de l'Aragon et ceux de la province d'Alicante. En mourant, il laisse encore inédites des études sur les Oursins de la Perse et sur ceux de la Sardaigne que, grâce à la collaboration de notre confrère M. Gauthier, nous connaîtrons prochainement.

As M. Emile Blanchard recalled in eloquent terms before the

Academy of Sciences, Cotteau had before his eyes all the specimens of sea

urchins collected in the different parts of the world. "Go," he said, "from

London to San-Francisco; go from St. Petersburg to Sydney; in every city

where there is a museum of natural history, if you ask: do you have sea-urchins?

the curator will never fail to answer: certainly we have sea-urchins and

still they are determined by M. Cotteau."

It is impossible, in this rapid overview, to indicate all

the progress that our colleague has made in echinology and in particular

to enumerate the new species or even only the new genera that he has made

known. The number is considerable and all the scholars that the question

interests will always be able to find them easily in his own works. It is

only appropriate to insist here on the scrupulous care with which these

genera and species were studied, on the truly scientific method followed

by him in his descriptions and classifications, and finally on the

philosophical idea which inspired him in the distinction and grouping of

species. Cotteau, like most of his former teachers and friends, firmly believed in the independence and fixity of species. The meticulous study he made of the fossil Echinids had, he said, confirmed him more and more in this belief. Although placed on the lower degrees of the scale of beings, the Echinids provide, according to him, in this serious question, arguments of an incontestable value. Never, in particular, do we find traces of the successive modifications of pre-existing types transforming themselves according to the environments where they develop; never do we find any of those intermediate types which should have served as a passage between one species and another. Most genera appear without it being possible to find a similar form in the preceding epoch from which they could be descendants; similarly, when they disappear from the animal series, it is to become completely extinct. The types that replace them cannot, in any way, be attached to them.Pénétrés de ces idées et désireux d'en fournir la justification, il cherchait attentivement, pour l'établissement de ses espèces, le caractère spécial susceptible de donner à chacune d'elles son individualité propre et de justifier son autonomie.

Obviously, he could not always succeed to the same degree.

Sometimes the amplitude of the variations that many species present

embarrassed him and made it difficult for him to specifically separate

certain forms having great affinities between them. He did not hesitate

then to admit his doubts sincerely.

It is undeniable that, in spite of his assertions, the

partisans of the mutability of species can find in his work, as in all

similar works, many arguments in support of their way of seeing. This is,

moreover, at least partly the consequence of the uncertainty in which, in

spite of the numerous definitions that have been given, we are still

concerning the entity of these groups of individuals that in natural

history are designated, rather arbitrarily, by the words genus, species

and variety. The conception that we have of these various groupings varies

singularly according to the kind of studies and the particular ideas of

each one.

Such differential characters which, for some naturalists,

may be only the result of a simple individual variation, may acquire in

the eyes of some others, a specific or even generic importance. In

reality, we have no certain criterium on this subject. We can never raise

any peremptory objection to these divergent ways of seeing. In

paleontology especially, arbitrariness reigns supreme and we have for

guarantee only the science, the circumspection and the sincerity of the

describer. Cotteau presented these guarantees to the highest degree. He was really without bias and moreover very tolerant for the ideas of others; also all the paleontologists, even those who, from the philosophical point of view, did not share his way of seeing, welcomed with confidence his conclusions.C'est toujours avec une attention consciencieuse et sans se laisser entraîner par aucune idée préconçue qu'il suivant, dans la longue succession des âges géologiques, les modifications incessantes de la faune échinitique, qu'il s'est attaché à montrer l'association des formes propres à chaque époque et à indiquer les types, assez rares, selon lui, et d'une longévité exceptionnelle, qui persistaient dans les époques suivantes.

As far as the general classification of Echinids and their

division into large groups is concerned, our colleague has always shown

the same prudent and measured scientific spirit. Carefully guarding

against rejecting all previously acquired ideas and upsetting the

nomenclature, he has been content to improve it prudently and

progressively.

Thus, having adopted in principle the four large families

recognized by Agassiz for the whole of the Echinids, he successively

admitted important dismemberments, to the point that, in his last work,

instead of the four primitive families, he recognized seventeen.

From the beginning of his researches on the fossil sea-urchins,

Cotteau had prepared himself to the perfect knowledge of their

organization by a thorough study of the currently living species. It is thanks to this knowledge of the details of their organism that he was able to make known to us many facts and many details ignored until then in the fossils, like the true orientation of the Salenidae, the constitution of the apex in many genera like Goniopygus, Glyphocyphus, Anorthopygus, etc.; then certain delicate organs like the apex of the gills, the apex of the gills, the apex of the gills, etc. Then certain delicate organs like the masticatory apparatuses, like the anal and buccal plates, so seldom preserved in the fossil sea-urchins; then finally of many teratological cases, curious anomalies of constitution, etc., etc.L'ensemble de l'oeuvre de Gustave Cotteau sur l'échinologie ne comprend pas moins de 5.000 pages et près de 1.600 planches. Toutes ces planches ont été exécutées par son fidèle et habile dessinateur, M. Humbert, et, comme l'a dit Cotteau lui-même, elles l'ont été avec un talent, avec une exactitude et une finesse de détails qui n'ont été surpassés nulle part, et qui facilitent singulièrement la parfaite connaissance et la détermination précise des espèces.

On this last point, allow me, Gentlemen, to stop a little

longer. It is important, in fact, to demonstrate here that the work of

Cotteau has not only achieved purely zoological progress, but that it has

rendered the most signal services to general geology. All the

stratigraphers, indeed, will approve me, without any doubt, when I say how

much the Sea Urchins are currently invaluable for the distinction and the

determination of the geological horizons. The Cephalopods with chambered

shells are the only ones that can compete, in this respect, with the

Echinids. Perhaps the usefulness of the latter is even greater?

The cloisonné cephalopods, indeed, because of their mode of

existence and their mode of dispersion in the sediments, are considered

characteristic fossils par excellence. The stratigraphers grant them all

their confidence, in preference to the other fossils; but it should be

considered that we cannot use them any more below the secondary grounds.

It seems moreover that Ammonites and Echinids complete and

supplement each other to help us in our stratigraphic research. One cannot argue that there is a complete incompatibility between these two categories of fossils since, for several genera at least, Echinids appear in certain beds, simultaneously with Ammonites, but it is no less real that, almost generally, these two faunas are more or less exclusive of each other. Without going far to seek examples which abound, if we look near us, in our secondary grounds of the Basin of Paris, we see that always the assizes very rich in Ammonites, are deprived of Sea Urchins and vice versa. Our stages of the Lias, the Callovian, the Oxfordian, the Portlandian, the Albian where Ammonites abound, are excessively poor in Echinids. On the contrary, the Bathonian, the Rauracian, the Astartian, and then the entire Upper Cretaceous are very rich in Echinoderms, with the almost complete exclusion of Ammonites.

How in particular would we have succeeded in distinguishing

the successive horizons of the great massif of our white chalk without the

help of Micraster, Echinocorys and other Echinids?

In the tertiary terrains, the role of Echinids is even more

important and even becomes quite preponderant. Also, we must sincerely

regret that the work of the master was stopped at the half of these

grounds and that we are thus deprived of the complete series of the

miocene and pliocene echinological fauna. The sea urchins, as Cotteau himself pointed out, lend themselves better than most other fossils to a rigorous specific distinction. Because of the complication and multiplicity of details to be studied on their calcareous skeleton, their taxonomy acquires a degree of precision that we could not reach in the other fossils. Whereas in the Molluscs, for example, the general form, the ornamentation of the shell and the details of the columella or the hinge, when one has the good fortune, rather rare, to be able to study them, are more or less the only elements of which the paleontologists have most often to distinguish the kinds and the species, in the Echinids, on the contrary, at the same time as an extremely variable form and infinite differences of structure and microstructure, one still has to study many organs or external characters such as the ocellar plates and the oviductal plates, the ambulacres and their pores, the various impressions, the fascioles, the peristome and the periproct, whose position is so variable, the apical apparatus, the tubercles being used as support to the radioles, the radioles themselves which sometimes were enough, because of their differences, to motivate the distinction of certain species whose tests however appeared identical.

Cotteau has taken great care to describe all these organs

in the diagnoses of each species and to show them to us in excellent

figures. Also his species are generally well defined and easily

recognizable. Moreover, he has always taken the precaution of indicating

in a detailed way the various geological horizons inhabited by each of

them, and all the localities of France and abroad where their presence has

been noted. In these conditions one must recognize that, thanks to him, the Echinids became one of the most powerful auxiliaries of the stratigraphy, to the point that, as he said it himself, a debris of Sea Urchin is often enough to fix the uncertain age of a bedding. X

The work of Cotteau, apart from his work on the Echinids,

to be less important than these, does not constitute less a considerable

whole sufficient to establish, with him alone, the reputation of a scholar.

It consists first of all, as far as the original works are

concerned, of numerous notes on the geology of the departments of the

Yonne and the Aube, on fossil Molluscs, on archaeology, etc. Several of

these notes were devoted to the study of the geology of the Yonne. Many of

these notes were devoted to unravelling the complicated stratigraphy of

our coral stage, and to establishing its relationship with the Oxfordian

layers from below and with the Astarte layers from above. Others were

devoted to the study of our Tertiary and Quaternary terrains, to the mode

of formation of the caves of the Cure valley, to the origin of our erratic

blocks, etc.

In his studies on the Echinids of the Yonne, he preceded

the description of the species of each stage with a geological study of

the layers which contain them and, as in our department, which is very

privileged in this respect, all the stages of the secondary terrains are

richly represented, it resulted that Cotteau, with the help of a few

collaborators for the upper stages, described the very complete series of

the secondary terrains. Later, to accompany the palaeontological memoir of M. de Loriol on the fauna of the Portlandian stage of the Yonne, he wrote a very detailed note on the stratigraphy, lithology and geographical extension of the layers of this horizon.

Among the works of an analytical nature, we must mention,

in the first place, that important series of annual reports on the

progress of geology, which he published regularly for twelve years to

satisfy the demands of the Institute of the Provinces.

These reports, which summarised in a clear and concise

manner all the work published in France during the previous year, were

always a legitimate success. M. de Caumont considered them as the most

important communication of his scientific congresses.

The Revue de Géologie, which MM. Delesse and de Lapparent

published for a long time in annual issues, continued Cotteau's idea by

extending it and including the scientific movement abroad.

Then there were reports on the museums and exhibitions of

natural history in the province. The first of these reports was written in

virtue of a special mission entrusted to our friend by the Institut des

Provinces. He visited the museums of Tours, Poitiers, Niort, La Rochelle,

Angoulême, Bordeaux, Dax, Mont-de-Marsan, Bayonne, Pau,

Bagnères-de-Bigorre, Tarbes, Toulouse, Montauban and Auch, and for all

this he was paid a somewhat paltry allowance of 200 francs.

Later he extended these reports to the museums of

Switzerland and Southern Germany. Finally, we must mention here his numerous reports on scientific congresses and meetings of learned societies, which Cotteau gave mainly to our Société des Sciences de l'Yonne and thanks to which this Society was so well informed about the movement of natural sciences, then the lectures on various subjects which he gave either in Auxerre itself or in the congresses of the French Association, and, to finish this long enumeration, numerous tracts on prehistoric archaeology, of which the main one, a volume of more than 300 pages, illustrated with numerous figures, was written in 1889, at the express request of his publisher, M. Baillière, for the Bibliothèque scientifique contemporaine, and was a considerable success.

XII

This is the broad outline of Gustave Cotteau's work, as it

can be summarised here. But, in order to do him the justice that is due to

him, we must also take into account the many services that he rendered

more or less directly to science.

When d'Orbigny, for example, was going to begin the study

of a class of fossils, he informed Cotteau who immediately set out to

provide him with materials or stratigraphic information. The considerable

number of species that we find bearing Cotteau's name in d'Orbigny's

catalogues testifies to the importance of the discoveries made by him.

It is to his initiative and thanks to his fruitful

intervention that we owe many important works on the department of the

Yonne, such as the description of the fossil fishes of this department, by

M. Sauvage, that of the plants of the bathonian layers of Ancy-le-Franc

and of our coral stage by de Saporta, the catalogue raisonné of the

Spongitarians of the neocomian stage published, in 1861, by de Fromentel

in the Bulletin of the Society of the Sciences of the Yonne, the

palaeontological memoir of M. de Loriol's palaeontological report on the

Portlandian stage and the even more important one by the same scholar on

the Astartean fauna of Tonnerre, those of M. Lambert on the Middle

Jurassic and on the Corallian of Tonnerre, and then numerous notes by

Hébert, Ebray, myself, etc. on various points in the department, on

various points in the department. I spoke earlier, on the subject of Cotteau's correspondence, of the letters that Professor Bayle wrote to him. There are some which show in a very convincing way with what devotion our fellow-member helped the studies of the learned professor. Bayle, who before undertook research on the Diceras, incessantly conjured him to provide him with new materials. "Il m'en faut", he wrote to him, "1,000, 10,000, 100,000 exemplaires et en grande vitesse."

I do not know exactly if our friend was able to supply him

with all these quantities, but what I do know is that to satisfy these

requests he had the hillsides of Coulanges, Crain and Merry-sur-Yonne

excavated at great expense and, if I believe some of the receipts that are

in my hands, he had to send at least 602 copies of Diceras. It is thanks

to these shipments that Bayle was able to make known the unexpected

diversity of these specific forms which, until then, had been hidden under

the single name of Diceras arietina.

In yet another circumstance, Cotteau rendered science and

our department a signal service. It was a question of Polypiers, of which

our Neocomian layers of the Yonne contain such beautiful and varied

specimens. Three specialists, Michelin, Robineau-Desvoidy and d'Orbigny

proposed themselves simultaneously to deal with these fossils. Michelin

wanted to add them to those of the sixteen localities already included in

his Iconogaphie zoophytologique, and he urged Cotteau, not only to

communicate his own materials to him, but to intervene with Dupin (d'Ervy)

and Robineau-Desvoidy so that they would send him theirs.

D'Orbigny, for his part, also requested them. He even

travelled to Saint-Sauveur and Auxerre and complained bitterly to Cotteau

that Robineau-Desvoidy had not wanted to give him anything, lend him

anything and hardly even let him look for them himself. Cotteau, embarrassed by this competition, multiplied himself to satisfy all his correspondents. He carried out research and even expensive excavations in our vicinity and thus managed to collect a considerable quantity of Polypiers.Il arriva cependant que Michelin, n'ayant pu obtenir tout ce qu'il désirait, renonça à les décrire ; Robineau-Desvoidy ne les décrivit pas davantage ; d'Orbigny, dans son Prodrome, en mentionna et en nomma un grand nombre, mais il ne put ni les décrire, ni les faire figurer. It was only ten years later that a fourth scholar, de Fromental, finally undertook this work. His memoir: Description des Polypiers fossiles de l'étage néocomien, was published in 1857 in the Bulletin de la Société des Sciences de l'Yonne. It covers 105 species, many of which bear the name of our friend and it was dedicated to him. This dedication is too much to his credit for me not to reproduce it here. " A Monsieur Cotteau, Monsieur, le département de l'Yonne, qui vous doit un important travail sur les Echinodermes, vous a révélé des richesses zoophytologiques d'autant plus précieuses que la plupart des fossiles que vous avez découverts appartiennent à des espèces nouvelles et non décrites. Vous avez eu l'extrême obligeance, sachant la part active que je prends à l'étude des Zoophytes, de m'envoyer votre belle collection de Polypiers néocomiens et je me fais un devoir d'en publier la description dans le Bulletin de la Société du département de l'Yonne qui en a fourni la plus grande partie. Croyez, Monsieur, que je n'oublierai jamais les excellentes relations que nous avons eues ensemble, et veuillez agréer la dédicace de cet ouvrage comme un faible témoignage de mon affection et de ma haute estime. Gray, 12 décembre 1856. De Fromentel. "

XIII

All these services rendered to science, all these personal

works so appreciated by the learned world, did not fail to attract to

Gustave Cotteau numerous and high honours.

If he worked a lot, he also experienced the joys of success

and the happiness of seeing the product of his work appreciated at its

true value.

As early as 26 August 1858, he was appointed correspondent

of the Ministry of Public Education.

In 1861, at the meetings of the learned societies of the

Sorbonne, he obtained a bronze medal, then, in 1863, a silver medal and,

in 1867, a gold medal.

On 10 August 1864, he was awarded the title of Officer of

the Academy and, on 25 March 1876, the title of Officer of Public

Instruction.

In the meantime, on 3 August 1869, he had been made a

Knight of the Legion of Honour.

In 1882, he was appointed curator of the museum of the city

of Auxerre.

In 1884, the Académie des Sciences awarded him the Vaillant

prize of 2,500 francs for his research on fossil Echinids. In 1885, on 12 July, the Société libre pour le développement de l'instruction et de l'éducation populaire awarded him a medal of honour for his numerous works in anthropology and archaeology.

n 1887 the Académie des Sciences elected him, in the midst

of many candidates, as a corresponding member for the section of anatomy

and zoology, and we have recalled above in what laudatory terms M. E.

Blanchard, the eminent rapporteur of the commission, had asserted his

titles to this high distinction.

On 25 November 1891, the Geological Society of London did

him the much sought-after honour of electing him as a foreign member in

place of Hébert, the learned and lamented professor of the Sorbonne, whom

we are honoured to count among our compatriots and among the former

students of our college.

In 1893, the Academy of Dijon awarded him the highest prize

it has, the gold medal, for his fine work.

If, finally, we recall that at each of the Universal

Exhibitions of 1867, 1878 and 1889, Cotteau was awarded a medal of honour

for his cooperation in their organisation and for his personal exhibitions

of objects of art and prehistoric archaeology, we will hardly have

finished with the long list of awards he has received, for it would

obviously be necessary to include among the highest awards the honour of

presiding over major scientific societies on several occasions. XIV

Almost all the great learned societies in France and abroad

have made a point of counting Gustave Cotteau among their members. We give

below, with the time of his admission, the list as we have been able to

establish it according to the letters or diplomas we have in our hands.

Perhaps we have omitted a few? We apologise to these societies and

attribute this omission only to the absence of sufficient information.

Among these societies, there are some that deserve special

mention because of the important position our colleague has occupied in

them.

First of all, it is our Geological Society of France, of

which Cotteau was a member for more than fifty-four years.

From that distant and brilliant period of the Society, when

the seat of the presidency was occupied by scholars such as Brongniart,

Constant Prévost, Elie de Beaumont, Alcide d'Orbigny, d'Archiac and so

many others no less illustrious, very few members still remain among us.

With Cotteau we had the regret to lose two of them in the course of this

year, MM. Loustau and de la Sicotière, and at present, only three remain,

who are older than him in the Society. These venerable confreres, whom I

wish to greet here, will forgive me, I hope, for mentioning their names.

They are : M. Parandier, our dean, who joined the Society in 1833; M.

Victor Raulin, admitted in 1837, and finally M. Daubrée, admitted, like

Cotteau, in 1839. In 1874, Gustave Cotteau, although not a resident of Paris, had the honour of being elected President of the Society. The same honour was bestowed upon him again in 1886, and all our colleagues have kept the memory of the courtesy, authority and high competence with which he led our discussions and presided over our meetings.

He had long been a life member of the Society. Because of

his bequest to the Society and in accordance with our rules, he is to

become a member in perpetuity. His name will continue to figure among us,

and it will always be with fond memories that we will read him at the head

of our lists.

Another Society in which Cotteau occupied an even more

considerable position is our Society of Historical and Natural Sciences of

the Yonne. In 1847, he was one of its founding members and one of its

organisers. The first Bulletin of this Society already contains four

scientific notes by him and, since that time, not one of the volumes has

been published without him inserting some memoirs.

Successively secretary, then vice-president for fifteen

consecutive years, he was elected president in 1883 on the death of

Ambroise Challe and, from that day on, he was constantly re-elected until

his death.

Cotteau was truly the soul of this Society, which he was

particularly fond of, and he contributed greatly to making it one of the

most active, hard-working and highly regarded in France. It was to it that

he reserved all those reports of international or other congresses, of

learned meetings of all kinds, which, as he himself said, were intended to

popularise scientific ideas, and to keep the Society over which he

presided abreast of the great intellectual movement and of the zoological,

geological and archaeological discoveries of our time.

His loss was deeply felt in this Society, and the touching

testimonies of affection and admiration, which were given to him, at the

time of his death, by the vice-presidents, were really the translation of

the unanimous feelings of all the members.

Among the great societies in which Gustave Cotteau also

played an important role, we should mention the French Association for the

Advancement of Science, at whose annual congresses he regularly attended,

where he gave public lectures and where he most often chaired the geology

section; Then the Zoological Society of France, in whose Bulletin he

published annually his very interesting fascicles on new or little known

sea urchins, and of which he was elected president in 1889; and finally,

the Institute of the Provinces, where he was admitted as a full member on

25 April 1859, and where his ever-growing position soon became one of the

most considerable.

Elected secretary on 23 April 1865 for the science section,

he became in the same year president of this section and, on 14 February

1868, he was appointed secretary general of the Society.

His communications, especially his reports on the progress

of geology in France, were, as I have said, one of the main attractions of

the annual scientific congresses that the Institut des Provinces organised

in the main cities of France and also of the meetings of delegates of the

learned societies that he directed, which were also called the General

Council of the Academies and which were held at the time in the Rue

Bonaparte during the Easter holidays.

The numerous letters that de Caumont, the director of the

Institute, wrote to him constantly, all testify to the important role of

our fellow member in the organisation of these congresses and meetings. I only want to quote a short passage which suffices to summarise them all. "Your letter worries me," he wrote to him on 18 July 1870, "what will we do without you? How can we find a chairman for natural history, if your foot ailment stops you on 31 July? I am anxious and await better news."

XV

As can be seen, Gustave Cotteau's life was everywhere and

always filled with work. Those who saw him only in one of his spheres of

action could not realise the enormous amount of activity and labour he

expended.

It is to show this to everyone, to highlight this constant

dedication, this uninterrupted work that the present notice is intended.

Our late friend, moreover, was not satisfied with deserving

science during his lifetime, he wanted to serve it even after his death by

his generosity and by the testamentary provisions he made.

You already know these provisions. He bequeathed 3,000

francs to the Geological Society and 3,000 francs to the Yonne Science

Society.

is precious natural history collections are preserved for

science. His library alone will be dispersed and will become part of the

common fund and the general circulation.

The collection of Echinoderms of the present time was

bequeathed to the Museum of Natural History, which it enriched with

numerous species that our great scientific establishment did not yet

possess.

The collection of fossil echinoids, the most important of

all, was bequeathed to the Ecole des Mines where, united with the Michelin

collection, it will, as the learned director of the Ecole des Mines, M.

Haton de la Goupillière, recently said, constitute an unparalleled

collection, with which it will be difficult for any other museum to

compete.

The conchyliology collection has not yet been allocated. As for the considerable collection of stratigraphic palaeontology that Cotteau had assembled, as it is of particular interest to the department of the Yonne, it was to a compatriot that he saw fit to bequeath it. It is in Auxerre that I have installed it, and that I am going to join it to the no less considerable collection that I have been amassing myself for 40 years and which will complete it very happily by the addition of the palaeontology of numerous regions that our colleague has not had the opportunity to explore.

My age, unfortunately, will not allow me to make full use

of this collection of Cotteau's, but, in accordance with the ideas and

habits of our late friend, it will continue to remain widely open to all

workers who wish to use it. All those of our colleagues who, having not

forgotten the path to Auxerre, would like to come and draw on it for study

material, will always be welcome. They will find the memory of their friend everywhere and, passing in front of his house, now deserted, on which they will cast a sad glance, they will be able to go, not far from there, to the cemetery where he rests next to those who were dear to him, to salute the tomb of this great man of science and this great man of good who was Gustave Cotteau. ________________

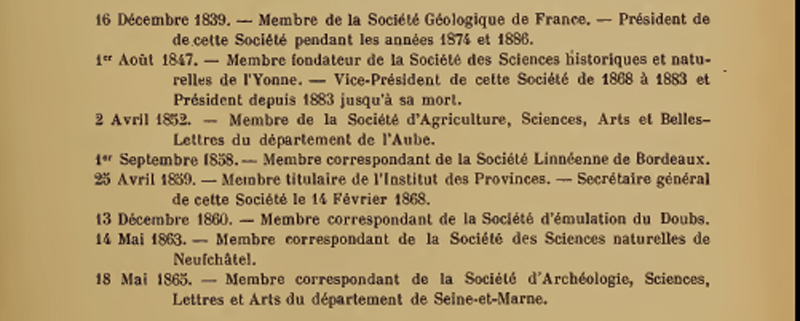

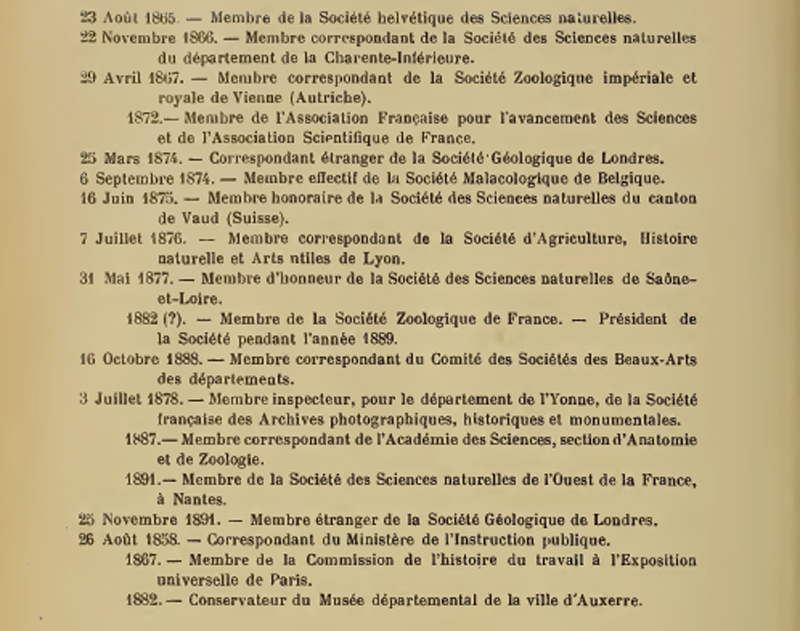

LIST OF SCIENTIFIC SOCIETIES OF WHICH GUSTAVE COTTEAU WAS A MEMBER

________________

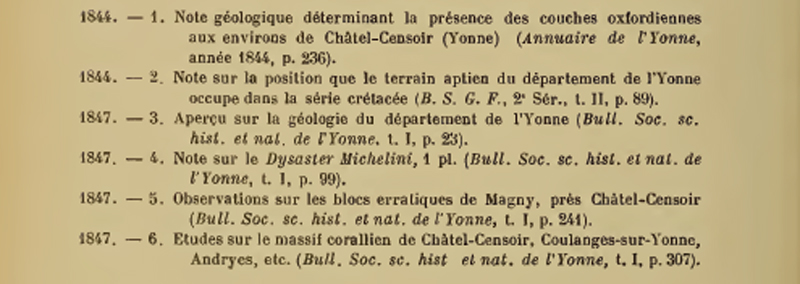

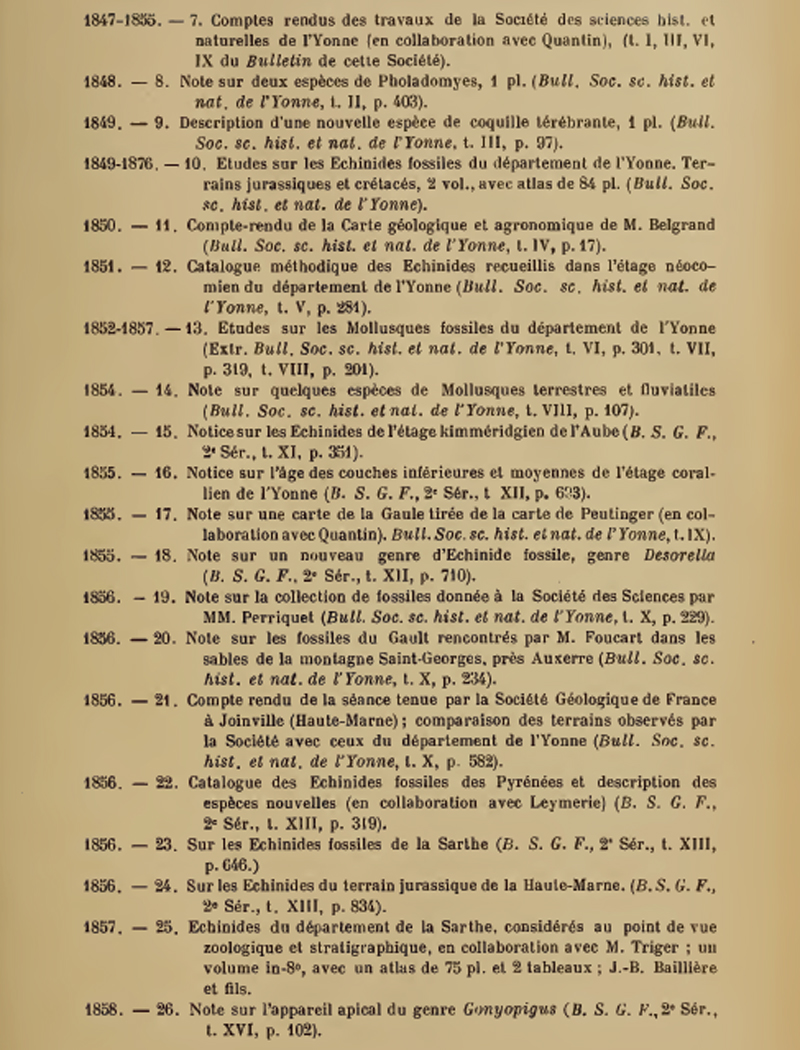

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF SCIENTIFIC WORKS PUBLISHED BY GUSTAVE COTTEAU

________________ |